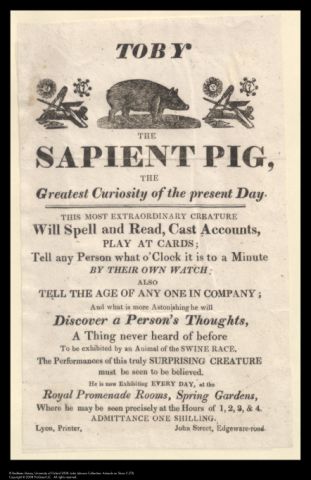

Billed as ‘the greatest curiosity of the present day’, Toby the Sapient Pig trotted into the limelight around 1817. He made his London debut at the Royal Promenade Rooms, in the Spring Gardens, where he captivated audiences with his promises to ‘spell and read, cast accounts, play at cards; tell any person what o’clock it is to a minute by their own watch… tell the age of any one in company’, and, most remarkably, ‘discover a person’s thoughts’, a trick indeed ‘never heard of before to be exhibited by an animal of the swine race’. Unsurprisingly, his enterprising handler Mr. Hoare was a former magician, who had turned to training novel animal acts (he would later appear in company with a Learned Goose).

There had been a previous wave of performing pigs in the late 18th century, but something about Toby appears to have particularly gripped the public imagination. Verses were written comparing him favourably to the greatest actors of the day, like Edmund Kean, and ‘Toby’ quickly became the generic name for all of his porcine competitors. His fame was such that, boasting he was ‘the first of my race that ever wielded the pen’ (an earlier literary pig had merely dictated its memoirs), Toby even wrote his own autobiography, The life and adventures of Toby, the sapient pig: with his opinions on men and manners. Written by himself (London, c. 1817).

Embellished with a frontispiece showing ‘the author in deep study’—or Toby settled comfortably in a pigsty with his nose in a book—the work was full of playful conceits. Describing his father as an ‘independent gentleman, who roamed at large’, and his mother as a ‘spinster… of a prolific nature’, Toby mused on the idea that his unusual talents resulted from his mother’s love of books:

‘My mother, in the early stages of her pregnancy, unwittingly entered a gentleman’s flower garden; where … she came obliquely to the entrance of his library…she entered, and in a short time cast her eye over the numerous volumes it contained; such was her haste, she disordered some, while others she minutely perused, nay absolutely bereived [sic] of their leaves, chewing and swallowing them, so great was her avidity’.

Toby told of being talent-spotted at a young age by his trainer (who made him a special cart to ride around in), claimed to have been named for whether he might be famous or not in a pun on Hamlet’s soliloquy ‘To be, or not to be’, and described an upbringing to rival that of any clever schoolboy. He also talked at length about the performance advertised in this very handbill, and confessed that he felt nervous before his London debut, convinced it would ‘make me or mar me for ever’. Happily for Toby, he was apparently a raging success:

‘…the house was crowded at an early hour by persons of the first rank and fashion: such an assemblage of beauty I had never before witnessed. My first appearance was greeted with loud and reiterated plaudits; from every part handkerchiefs waving—fans rapping—placards exhibited; in fact, the tumults of applause were greater than ever was known before.’

Priced at one shilling, Toby’s magnum opus was printed and sold—and, one suspects, also authored—by Nicholas Hoare, Toby’s canny trainer and manager. The autobiography was, of course, also a powerful advertisement for Toby’s performances, as suggested by the verse with which ‘Toby’ chose to conclude his tale. Supposedly written by a gentleman much moved by the sight of Toby spelling out his letters, it was carefully calculated to entice curious punters:

His symptoms of sense, deep astonishment raise,

And elicit applause of wonder and praise…

Of the crowds who the Sapient Toby have seen,

Not one of them all disappointed have been;

But all to their friends have been proved to repeat,

That a visit to Toby, indeed is a treat.

But then, for a shilling, who wouldn’t queue up for a look at a mind-reading pig called Toby? – Amanda Flynn

Images:

Toby the Sapient Pig. John Johnson Shelfmark: Animals on Show 2 (70). ProQuest Durable URL

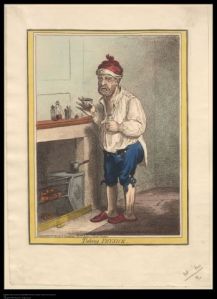

The wonderful pig of knowledge. John Johnson Shelfmark: Animals on Show 2 (74). ProQuest Durable URL

Copyright © 2009 Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Reproduced with the permission of ProQuest. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Comments are welcome for sharing with other users, but regrettably the editors of Curators’ Choice are not necessarily able to respond to enquiries.

Posted by johnjohnsonproject

Posted by johnjohnsonproject