The Chocolate Girl (known also as La Belle Chocolatière, or Das Schokoladenmädchen) is one of the most famous works by the Swiss artist, Jean-Etienne Liotard (1702-1789), and depicts a pretty maid serving a tray of hot chocolate.

The charming story behind the commission of the painting reads like a romantic fairy-tale. It is thought that the girl in the picture, Anna Baltauf, lived in Vienna and worked as a server in one of the chocolate shops which had become hugely popular throughout Europe during the 18th century. As the daughter of an impoverished Viennese knight, she had little chance of good marriage, however in the summer of 1745, a young Austrian nobleman named Prince Dietrichstein visited the shop. He fell in love with Anna and asked her to marry him, despite his family’s objections, and so the chocolate girl became a princess. As a wedding present to his bride, the prince commissioned the portrait from Liotard, an artist of the Viennese court. Anna is shown in the maid’s costume she was wearing when her future husband first saw her.

Das Schokoladenmädchen: the original portrait by Jean-Etienne Liotard

It is impossible to say just how much truth there is to this tale, however it is certain that in 1881 Henry L. Pierce, then president of the Walter Baker chocolate company, visited the painting in the Dresden Art Gallery and was captivated by it and by Anna’s story. He immediately registered La Belle Chocolatière as one of the first US trademarks and the image has graced the company’s boxes and packaging ever since. The original portrait of Princess Dietrichstein, the Chocolate Girl, still hangs in the Dresden gallery, where it remains one of the museum’s most popular attractions. – Ken Gibb

Images:

The chocolate girl. John Johnson Shelfmark: Cocoa, Chocolate and Confectionery 5 (54) (ProQuest durable URL)

Copyright © 2009 Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Reproduced with the permission of ProQuest. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Comments are welcome for sharing with other users, but regrettably the editors of Curators’ Choice are not necessarily able to respond to enquiries.

Posted by johnjohnsonproject

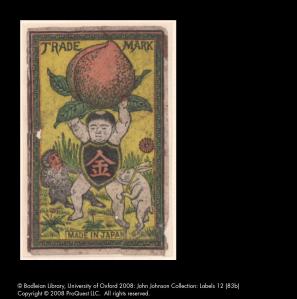

Posted by johnjohnsonproject  The story of Momotarō, although largely unfamiliar in the West, is a well known and loved Japanese folk-tale. Momotarō (often directly translated as ‘Peach Boy’) was the miracle child of an elderly couple who had not been favoured with the good fortune of having their own children.

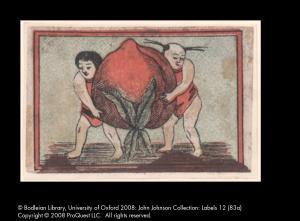

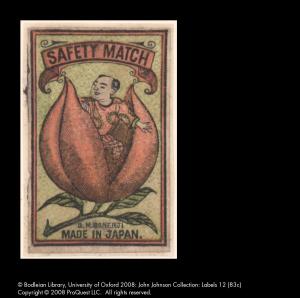

The story of Momotarō, although largely unfamiliar in the West, is a well known and loved Japanese folk-tale. Momotarō (often directly translated as ‘Peach Boy’) was the miracle child of an elderly couple who had not been favoured with the good fortune of having their own children.

– Elizabeth Mathew

– Elizabeth Mathew