A Mapping Crime case study by Rosalind Crone, The Open University.

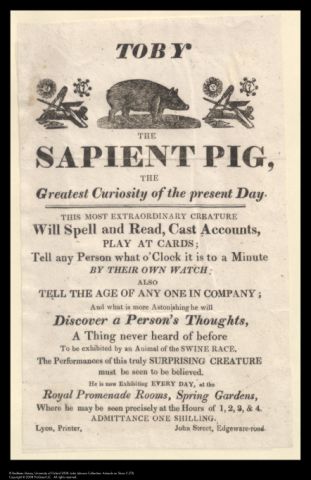

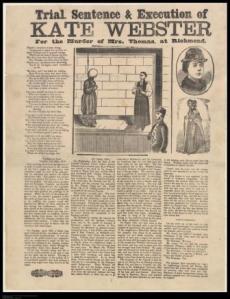

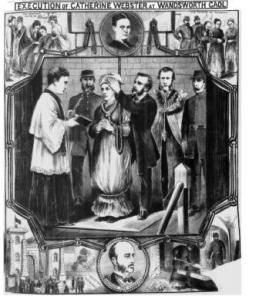

Crime broadsides are often said to represent the poor man’s newspaper in the nineteenth century. By the 1820s at least, printers had established a specific formula whereby a series of cheap, but highly decorous sheets of various sizes were produced for notable, especially violent crimes, capturing the event, the trials of the accused and the moment of his or her execution. The resources linked to the large number of crime broadsides in the John Johnson Collection as part of Mapping Crime highlight the relationship of these sheets to the newspaper and periodical press of the time, where these crimes were similarly reported.

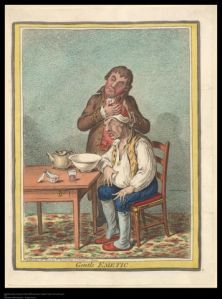

An edition of the Newgate Calendar from 16th September 1824, including the trials, and sentences, of the prisoners tried at the Old Bailey, this Sessions... together with the lamentation of those who are cast for death.

However, the resources linked to the broadsides also show that for at least a significant cluster of gruesome crimes the memory of these events was fanned by various cultural phenomena. In other words, a number of criminals were kept alive in popular culture for long periods after their deaths. This is, at first, most obvious in the links to the online Newgate Calendar. At least ten nineteenth-century criminals who feature in the broadsides in John Johnson also have entries in the Newgate Calendar: apart from two forgerers (Fauntleroy and Hunton) and one traitor (Thistlewood) the rest appear to have achieved notoriety through the crime of murder. The Newgate Calendar was a collection of biographies of criminals, most of whom were British and active from the eighteenth-century onwards. The publication first appeared in the 1770s, and although it was based on earlier, similar voluminous collections, it was more lavish and moralistic than anything that had appeared before with a price tag which suggested a more affluent audience eager to include the books in their libraries. The edition which features as part of the Mapping Crime resource was published as late as 1926, highlighting the persistent demand for both the publication and stories of significant crimes from times past.

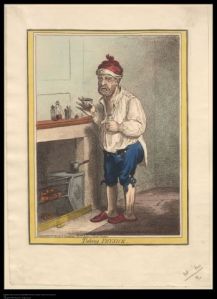

The Rugeley poisonings... The trial of William Palmer, at the Central Criminal Court, London, for poisoning John Parsons Cook...

Newgate Calendars were not the only publications produced in the wake of a criminal scandal with the aim of generating high sales from a public anxious to keep the memory of the crime alive. Internal links within the John Johnson Collection supplied as part of Mapping Crime highlight the production of a range of more durable sheets, pamphlets and volumes which brought together the key elements of the crime and its punishment and, unlike disjointed broadside or newspaper reports, presented the events as a digestible narrative. Many of these publications were produced by established newspapers as way of generating extra revenue. For instance, attached to the broadside printed for the execution of the infamous serial poisoner, William Palmer, at Rugeley in 1856 is the forty-page pamphlet produced by the Illustrated Times complete with the transcript of the trial, memoir of the prisoner and sixty illustrations. Similarly, items connected with the execution of James Blomfield Rush for the murders at Stanfield Hall include the series of engravings commissioned by the Norwich Mercury at the conclusion of the trial. Evidence from other historical sources suggests that some purchasers would use these illustrations to decorate the walls of their dwellings.

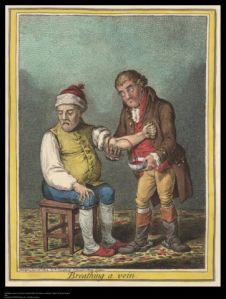

The examples of such pamphlets, volumes and other types of crime ephemera contained in the John Johnson Collection represent just the tip of the iceberg. Following the link provided to the British Library Newspapers reveals the extent of this practice. For example, after the execution of Frederick and Maria Manning for the murder of their lodger, Patrick O’Connor, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper advertised the publication of ‘The Trial of the Mannings’, reminding readers to ask the newsagent for ‘Lloyd’s Edition’. Those newspapers that did not publish their own pamphlets on famous crimes did not refrain from advertising those produced by others. Searches in British Library Newspapers for ‘Bishop and Williams’, the metropolitan Burkers (or body snatchers), active during the early 1830s, returns advertisements in the Morning Post for Pierce Egan’s book, The Murder of the Italian Boy, published in December 1831 and sold for 1 shilling sixpence.

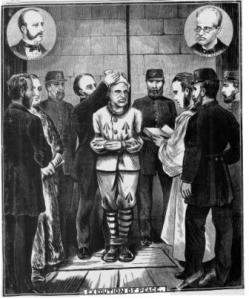

Books and pamphlets were not the only form of criminal legacy in the nineteenth century: links in the Mapping Crime resource also draw our attention to the performative characteristics of the legacies of the executed. Audiences could experience and remember a crime through its performance, not just through reading. The additional resources from the John Johnson Collection which appear alongside the broadside printed for the trial of William Corder are particularly instructive. Corder murdered his paramour, Maria Marten, in the Red Barn located in a Suffolk village in 1826; it was, more or less, a straightforward domestic crime. However, the discovery of Maria’s body apparently through the prophetic dreams of her step-mother ensured the crime gained notoriety throughout the country. By the time Corder was executed in 1828, the murder had become a popular melodrama played in theatres all over Britain. One of the playbills from the Lincoln Theatre survives in the John Johnson Collection.

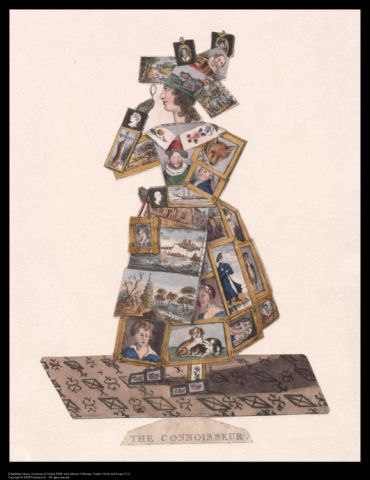

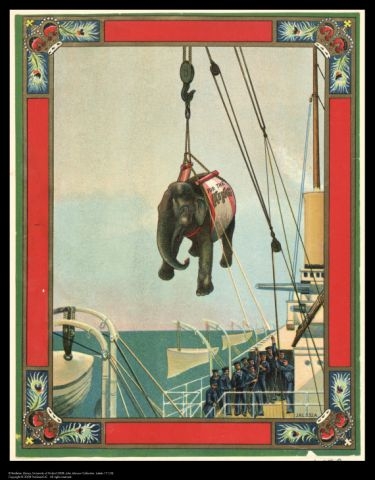

As does a catalogue from a waxwork exhibition on Pentonville Hill in London which advertised a ‘Cyclorama’ of the tragedy, treating viewers to key scenes of the murder. This link provides strong inducements to dig deeper. After all, the most famous waxwork exhibition in London, Madame Tussaud’s, featured a chamber of horrors which contained effigies of some of the most famous criminals of the nineteenth century. Again, following the links in Mapping Crime to the British Library Newspaper resource reveals a treasure trove: searches for specific criminals from the John Johnson Collection at times returns results which contain advertisements for the addition of wax effigies of these men and women to Tussaud’s ghastly chamber. Only a month after the execution of James Greenacre for the murder of his former lover, Hannah Brown, the Morning Post published this advertisement: ‘The Execrable Greenacre. Madame Tussaud and Sons, anxious to obey the wishes of their numerous visitors, have completed a full-length model of the fiend Greenacre. The likeness, taken from the best authority, represents him as he appeared at his trial’.

It is clear that a range of cultural phenomena existed to keep alive the memory of a select number of criminals in the nineteenth century; but were memories kept alive? The impact of these publications and performances is first evident in the broadsides themselves. Broadside authors at times made reference to notorious past crimes when reporting on a current tragedy, perhaps with the intention of creating a similar sensation out of the crime at hand. Mapping Crime highlights some of these links. When news broke of the discovery of a horribly dismembered and burnt corpse in aSurrey barn in 1842, broadside printers immediately compared the events to those of the Greenacre-Brown tragedy of 1837. One author stated Daniel Good’s appalling murder of Jane Jones ‘in the annals of crime, has only been equalled in atrocity by that of Hannah Brown, by Greenacre, and that of Mr Paas, at Leicester’. Connections between past and present murders could also be used to illustrate the didactic value of crime. Eliza Grimwood, for example, did not take warning from the murder of Maria Marten by William Corder, despite being ‘on a visit at a friend’s in the neighbourhood and the first person who entered the Red Barn and saw the mangled corpse of that ill-fated girl’. Instead, Grimwood went on to lead a reckless, immoral life and hence suffered a similar fate.

Finally, there is some very slight evidence that ordinary people at times invoked the names of famous murderers to describe particular human interactions, especially violent ones. Some of this evidence can be found in the transcripts of trails at the Central Criminal Court housed at the Old Bailey Online. Mapping Crime links crime broadsides directly to trials. But searching for the names of specific criminals generally in the Old Bailey Online database highlights the use of those names in other trials to describe violent encounters. For example, After the especially gruesome murder and mutilation of Hannah Brown by James Greenacre in 1837, several criminal trials followed in which witnesses claimed that the accused had invoked the name of Greenacre much to their concern and fright. During a robbery in June 1837, victim Catherine Crawford of the Hutchinson Arms in Ratcliffe claimed that the thief stated: ‘“If you do not give [the money] to me, it will be the worst day’s work you ever did, for I will serve you as Greenacre served Mrs Brown’ – I am quite sure he used that expression – he repeated several times about Greenacre, and I was very much alarmed’.

Images:

Newgate calendar. Including the trials, and sentences, of the prisoners tried at the Old Bailey, this Sessions. Together with the lamentation of those who are cast for death. John Johnson Shelfmark: Broadsides: Murder and Executions folder 1 (2). ProQuest durable URL

The Rugeley poisonings… The trial of William Palmer, at the Central Criminal Court, London, for poisoning John Parsons Cook : With a complete memoir of the prisoner, and a full account of the numerous cases of poisoning in which he is suspected to be implicated. Illustrated with sixty engravings, comprising… every place or object of interest connected with these startling crimes. John Johnson Shelfmark: Broadsides: Murder and Executions folder 11 (36). ProQuest durable URL

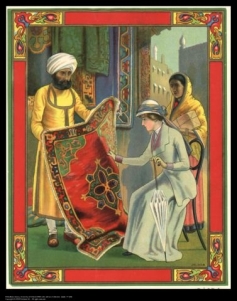

The trial of Corder, for the murder of Maria Marten, at Polstead, Suffolk. John Johnson Shelfmark: Broadsides: Murder and Executions folder 5 (11). ProQuest durable URL

An entire new exhibition, at 16, Pleasant Row, Pentonville Hill, near Battle Bridge [A beautiful cyclorama of the mysterious murder of Maria marten, by William Corder…]. John Johnson Shelfmark: Waxworks 3 (6). ProQuest durable URL

Copyright © 2009 Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Reproduced with the permission of ProQuest. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Comments are welcome for sharing with other users, but regrettably the editors of Curators’ Choice are not necessarily able to respond to enquiries.

Posted by johnjohnsonproject

Posted by johnjohnsonproject

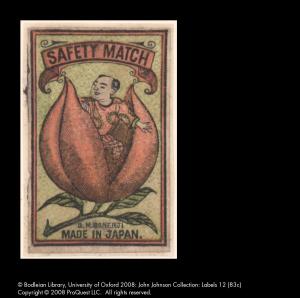

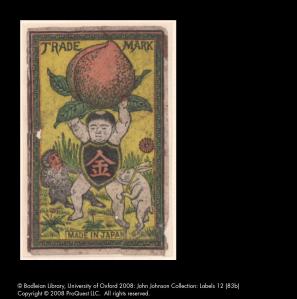

The story of Momotarō, although largely unfamiliar in the West, is a well known and loved Japanese folk-tale. Momotarō (often directly translated as ‘Peach Boy’) was the miracle child of an elderly couple who had not been favoured with the good fortune of having their own children.

The story of Momotarō, although largely unfamiliar in the West, is a well known and loved Japanese folk-tale. Momotarō (often directly translated as ‘Peach Boy’) was the miracle child of an elderly couple who had not been favoured with the good fortune of having their own children.

– Elizabeth Mathew

– Elizabeth Mathew