In 1819 Mary Green was found guilty of using counterfeit banknotes, a capital offence. Sentenced to death by hanging, Mary was executed on the morning of 22nd March on a scaffold constructed in front of the notorious Newgate Prison.

After “hanging the usual time” she was declared dead and her body released to friends for burial. To their astonishment, the “deceased” began to show signs of life. A doctor was quickly summoned and Mary was soon brought back to her senses.

Surprisingly, Mary appears to have suffered few lasting effects from her unfortunate ordeal. She is believed to have taken another name and started a new life in Canada. She died for the second, and final, time in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1834.

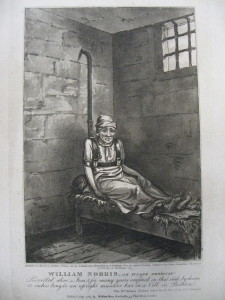

There are several other recorded instances of surviving the death penalty, the most famous tale being that of John “Half-hanged” Smith, hanged at Tyburn on 24th December, 1705. Capitally convicted for robbery, Smith was granted a reprieve while he was actually hanging on the scaffold. Having hung for 15 minutes or more, Smith was cut down and returned to life.

When asked what it felt like to be hanged, Smith reported seeing “a great blaze or glaring light that seemed to go out of my eyes in a flash and then I lost all sense of pain.” The pain, it seems, was reserved for his return to the living: “After I was cut down, I began to come to myself and the blood and spirits forcing themselves into their former channels put me by a prickling or shooting into such intolerable pain that I could have wished those hanged who cut me down.”

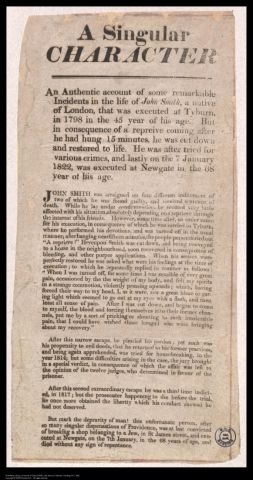

John Smith's story retold and updated for an 1820s broadside, complete with details of a fictional second hanging.

Smith apparently failed to learn his lesson – he was indicted for housebreaking at least twice more, narrowly avoiding the gallows each time.

Not every gallows survivor was as lucky as Mary Green or John Smith. A Mrs Cope of Oxford also lived through her death sentence in 1658, but this time the unsympathetic authorities simply insisted on mounting a second, more successful, attempt the following day. – Ken Gibb

Images:

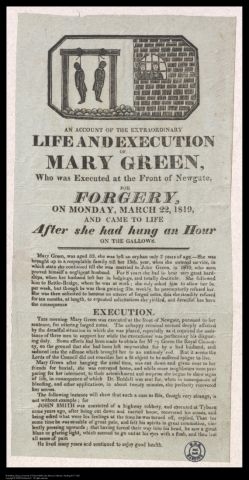

An account of the extraordinary life and execution of Mary Green. John Johnson Shelfmark: Harding B 9/1 (30)(ProQuest durable URL)

A singular character. John Johnson Shelfmark: Harding B 9/1 (40) (ProQuest durable URL)

Copyright © 2009 Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Reproduced with the permission of ProQuest. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Comments are welcome for sharing with other users, but regrettably the editors of Curators’ Choice are not necessarily able to respond to enquiries.

Posted by johnjohnsonproject

Posted by johnjohnsonproject