Medicine, in the early nineteenth-century, was not a pleasant experience for the patient. It was an age of “heroic” medicine that consisted of “copious bleeding and massive doses of drugs.”1 In 1804, James Gillray produced this series of satirical etchings that brilliantly charts the progress of disease in one unlucky patient…

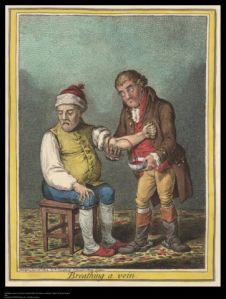

In ‘Breathing a vein’ the patient stoically begins his treatment with a course of bloodletting, or phlebotomy. Beloved by both physicians and quacks in the early nineteenth-century, it was a standard medical practice (and, indeed, one of the oldest, dating from classical antiquity). It entailed drawing blood from one or more of the larger external veins, such as those in the forearm, in order to ‘cure’ a disease and restore the body’s natural balance —frequently physicians would take so much blood in one sitting that the patient would be left faint and swooning. Gillray plays with cruel wit upon the contrast between the title, ‘breathing a vein’, which suggests a light and pleasant experience, and the reality, as indicated by the fountain of blood gushing from the patient’s arm and his glum expression.

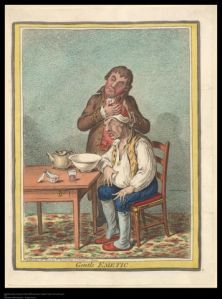

His condition not having improved, the patient is shown in the second print trying a ‘Gentle emetic’ instead—a dose intended to cause a bout of (anything but gentle) vomiting. The pale-looking patient sits beside a waiting bowl, while the physician holds his head in readiness.

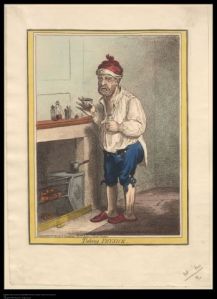

In the third of the series, ‘Taking physick’, the patient—looking ever more wretched—screws up his face against the sour taste of his medicine. Few effective drugs existed, and those that physicians did prescribe were sometimes more harmful than helpful—and the effects they produced were ripe for caricature. In this case the man is probably taking a laxative intended to purge the system of deletrious material. A labelled bottle is clutched in his hand, and two others stand waiting on the mantelpiece. Physicians would often prescribe drugs to be taken repeatedly, many times over in a day, and the patient’s unshaven, dishevelled state suggests that he has been subject to this treatment for some time. Indeed, Gillray’s sly depiction of the man’s unbuttoned trousers and trailing shirttails suggests that he has spent much of his treatment in close confinement with his chamber pot.

In the fourth print, ‘Charming well again’, the patient is finally recovered (probably despite rather than because of his treatment), and beams with delight. His relief seems due not just to feeling well again, but also to having exchanged his noxious doses for a hearty meal of roast chicken. Clearly, he hasn’t wasted a moment of his recovery on such trifling matters as changing out of his sick clothes and nightcap; having paused just long enough to tuck a napkin under his chin, he has launched straight into dinner. – Amanda Flynn

1Lois N. Manger, History of Medicine, New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., 1992, p. 205.

Images:

Breathing a vein. John Johnson Shelfmark: Trade in Prints and Scraps 8 (64). ProQuest durable URL

Gentle emetic. John Johnson Shelfmark: Trade in Prints and Scraps 8 (70). ProQuest durable URL

Taking physick. John Johnson Shelfmark: Trade in Prints and Scraps 8 (73). ProQuest durable URL

Charming well again. John Johnson Shelfmark: Trade in Prints and Scraps 8 (67). ProQuest durable URL

Copyright © 2009 Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Reproduced with the permission of ProQuest. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Comments are welcome for sharing with other users, but regrettably the editors of Curators’ Choice are not necessarily able to respond to enquiries.